The purpose of this paper is to look at the polar opposite ends in the Bollywood film industry in order to establish aspects of the industry. First, we will look into the history of Rajshri Productions and filmmaker Sooraj Barjatya and analyze how the traditional archetypes of ‘family-friendly’ and ‘evergreen’ films started and reached it’s peak from the late 80s to 90s. We will look at the different styles of the films by Sooraj Barjatya to understand how the formula for his films have primarily remained the same, despite the time that has passed.

Second, we will look into the history of films by filmmaker Anurag Kashyap and analyze each film’s extreme emphasis on India’s ‘real-world’ archetype, and its origin from the early 2000s till now. Additionally, we will look at how Kashyap’s films focus on topics such as drug addiction, violence, and poverty in a realistic light. Finally, we will look at films that share aspects from both Barjatya and Kashyap in order to establish what constitutes a middle-ground in the large Bollywood film industry. Barjatya has mastered romance and family and Kashyap has mastered thrillers in Bollywood. Therefore, we will use what we have learned (the elements of ‘ever-green’ versus ‘real-world’ films) to analyze aspects of the Bollywood film industry.

The Bollywood film industry, also known as Hindi-language cinema, originated in Mumbai, India in the 1930s up until today. But what kinds of films contribute to the Bollywood film industry? At one end of the Bollywood film industry is Sooraj Barjatya. Sooraj Barjatya is an Indian filmmaker and the chairman of Rajshri Productions. Prior to Barjatya’s introduction into the Bollywood film industry, it was evident that Bollywood’s commercially successful films outweighed the others.

These “other films” rely more on outlining each character’s psychology rather than progressing the plot with actions. These films tend to revolve around stories that are more representative of real life and real problems in India. Examples of these films would be films such as:

Pather Panchali (1955): The story of two young siblings’ impoverished lives in a village in Bengal

Kagaz Ke Phool (1959): The story of a renowned Indian director’s fall from fame after falling in love with an orphaned woman who outshines him as a star. This film was also a semi-autobiographical film based on the life of its director.

Examples of some of Bollywood’s commercially successful films are the following:

Mughal-e-Azam (1960): The story of a 16th century emperor falling in love with a dancer.

Teesri Manzil (1966): The story of a woman seeking revenge for the man that killed her sister, but then falling in love with him.

Sholay (1975): The story of two ex-convicts tasked with taking down a notorious bandit.

All of these films have a formula that makes each of them so successful:

These films capitalized on misogynistic viewpoints, such as with the showcasing of “item numbers''. “Item number” is a term that Bollywood has coined in order to define juicy musical numbers in which a woman dances as men rally around her, in an objectifying context.

Another thing that these commercially successful films had was lavish sets. This encompassed large houses, scenic shots, and over-the-top settings in dramatic musical numbers.

And finally, there was an obscure over-dramatization with acting, and heavy use of action sequences. It seemed as if filmmakers used these tactics in order to compensate for lack-luster plots.

Although these films were extremely commercially, and critically acclaimed, they were not necessarily meant for the entire family to watch together, until Barjatya entered Bollywood with his directorial debut with Maine Pyar Kiya (1989). Barjatya took the formula of commercially successful films in Bollywood and adjusted some factors in order to create his films. He made the films “clean” and action free. Barjatya’s films are now known as Bollywood cult-classics and some of the most popular films of all time from this industry.

Barjatya took out the “item numbers” and promiscuity from these films and replaced this factor with an “evergreen family friendly aspect”. You can see a direct reference to this change with the dance number, “Maye Ni Maye”, in HAHK (1994). While in parts of this dance number, we see the heroine, dance for the man she is vying for, this only lasts briefly. Eventually, the song ends up showing the male family members who were sitting, dancing with her as well. In this way, Barjatya made a subtle nudge towards “item numbers” and rejected its format by making this dance sequence end up as family friendly instead.

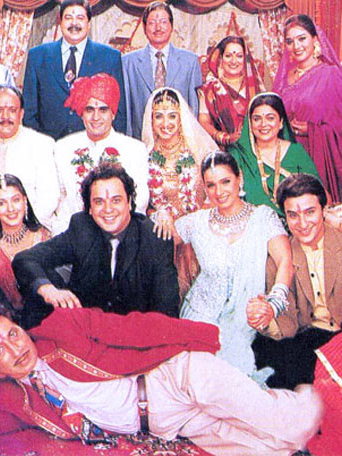

Patricia Uberoi analyzes the aspects of Barjatya’s films through her Ethnography analyzing Barjatya’s second film Hum Aapke Hain Koun…! (1994) (Uberoi, 2001). The reason that Uberoi analyzes this film is because Hum Aapke Hain Koun…! is one of the highest grossing Bollywood films of all time (Uberoi, 2001). Uberoi breaks down Barjatya’s formula in different categories such as: Clean Film, Ideal Indian Family, and the Voyeuristic qualities of a Happy Ending (Uberoi, 2001). These aspects are evident within all of Barjatya’s films. Uberoi defines Barjatya’s genre of ‘family’ film as “for a family audience and about family relationships, inclusive of, but much broader, than the true romance that provides its storyline” (Uberoi, 2001, p. 311).

In this way, any sense of vulgarity is removed from Barjatya’s films, and instead replaced with family friendly dance numbers. An example of this would be the song “Joote Do Paise Lo” from Hum Aapke Hain Koun…!. In this song, the guys side battle the girl’s side in a common South Asian wedding ritual. The women’s side steals the groom’s shoes and only returns them when the groom’s side has allocated money for them. In this quote on quote, “battle” the guys side and girls side dance and sing, taunting each other. Uberoi claims that this song is one of the many ways in which Barjatya chose to indirectly establish the sexual tension between lead characters, Prem and Nisha, while not being outwardly vulgar, and still making the song a fun watch for the whole family (Uberoi, 2001). This assumption is reaffirmed when in the end of the song, Nisha falls on top of Prem in a bedroom while fighting over the shoes.

All of Barjatya’s films depict an “Ideal Indian Family”. Specifically, Uberoi states: “Barjatya presents ‘a perfect utopia’—about ‘simple values and guileless people’. In other words, the films are not about the family as it is, but the family as people would like it to be” (Uberoi, 2001, p. 311). And there are so many layers to this aspect but it is important to Barjatya to showcase families in this particular light. These are all joint-families—meaning that even after the sons of the family get married, their wives move in with them, their parents, and extended aunts, uncles, maids, and so on. This creates a big household that only multiplies and this is what Barjatya is showcasing— a massive family where they all get along all the time. They also take on their conventional roles in relation to Indian stereotypes about gender and family. The wives are often seen as cooking and providing food for the men to an extent where the men are expecting it. The men are shown in offices, high positions within households, and this is even reflective in their staging. They are constantly staged over women, higher than women. The times in which Barjatya empowers women as leads within his films, is only when they are vying for the attention of a man.

However, Barjatya, tends to depict the women in his films often as submissive and quiet, and sporadically placing a loud and extroverted lead within his films as well. It's clear that Barjatya sees women only within the realm of their gender stereotypes—it is as if their only purpose within each of his films, is to serve and value the men around them. For example, in Maine Pyar Kiya (1989), when Suman goes to comfort Prem, after seeing that he is upset, she is rudely spoken to by him. Prem then smiles, and commands Suman to go get him food—no please or thank you. And then, what does she do...? She goes and gets it for him, and then other men proceed to ask her for ‘food’ as well.

Another aspect to this ‘perfect utopia’ of family is religion and family (Uberoi, 2001, p. 311). Each of his films largely prioritize culture and religion within the family, there are aspects of prayer and worship throughout each and every film. In Barjatya’s 1999 film, Hum Saath Saath Hai, the sons of the family sing a seven-minute song: “Yeh To Sach Hai Ki Bhagwan Hai”. This song revolves around the sons thanking their parents for the family values they have taught them, and saying how they have found God within their parents. In this way, Barjatya has tied in the aspects of respect and discipline—both aspects of an ‘ideal family’—with another important aspect, religion. Uberoi states that “these films show domestic rituals and family relationships as they once were and as they should be, but not as they presently are in a degenerate world” (Uberoi, 2001, p. 323-324).

Finally, there is a voyeuristic appeal of viewing these films, in the sense that the viewer is left leaving the theatre satisfied with the ‘happy ending’. Uberoi states that HAHK, along with Barjatya’s other films is “a film that has given immense pleasure and satisfaction to millions of Indian viewers” (Uberoi, 2001, p. 333). It provides the pleasure of spectacle, but amazingly does so without the usual formulaic ingredients of Bollywood movies: “blood and gore, sex and sadism. And it exploits erotic tension, short of explicit sexuality right through to the climax” (Uberoi, 2001, p. 310).

The expectation that is placed in the beginning of the film of the leads ending up together is fulfilled by the end of the film with the little to no obstacles. Additionally, Barjatya carries the trait of lavish sets and depictions of primarily an upper-class within popular Bollywood films. There are no financial obstacles. Uberoi states as well that Barjatya’s “overall impression of decency is its unembarrassed endorsement of the upper class, indeed affluent, lifestyles—no poverty or ‘simplicity’ here” (Uberoi, 2001, p. 319). In this way, the audience is able to walk away with the satisfaction of a ‘happy ending’ from a family friendly film. A film, about family, that they can watch with their entire family, and leave with lessons of respect, culture, and religion, instilled within their own children.

On another end of the spectrum, is filmmaker, founder of Anurag Kashyap Films Pvt. Ltd., and co-founder of Phantom Films, Anurag Kashyap. I believe Kashyap to be on the other end of the spectrum because he stands and showcases everything Barjatya does not: sex, violence, drugs, alcohol, and most importantly realism. Kashyap has always maintained focus on the real world and showcasing matters as he would believe them to play out in India as India is. For this reason, time and time again, Kashyap has faced issues and battles with India’s cinema censor board due to what the censor board calls “stubbornness” and what he calls “passion” (India today, 2009). Kashyap has been known to refuse to cut scenes from his films—these scenes often pertain to explicit sexual or violent contents. Unlike the previous films we have seen by Sooraj Barjatya, Anurag Kashyap does not capitalize on evergreen entertainment, he capitalizes on the representation of realism. Therefore, for Kashyap, cinema is not some "escape", but a chance to give the public a taste of how terrible the real world can be at times.

The 2012 two-part crime film, Gangs of Wasseypur, by Anurag Kashyap, centers around a son's dedication to seeking vengeance for his father's death; in the complicated realm of India's gangs and politics throughout decades. In the first scene of the film, a family sits around a television set, as they watch a drama serial about a happy family. In the middle of their viewing, the entire house suddenly gets shot at by a gang. Therefore, by showing the characters within the film viewing a piece of media, that is essentially the complete opposite of what Gangs of Wasseypur is about, they give a small nudge to this polar-opposite spectrum of content within Indian cinema.

Gangs of Wasseypur (2012) also sheds light on the corruption of politics and the police force within India—how it is so easy to manipulate the system, and how common it is to get screwed over by association. Additionally, the film can be problematic in the sense that it advocates for many to take the violent and aggressive approach. For example, Sardar Khan is seen as most successful, within the cinematic world of Wasseypur, when he kills and threatens others—sending the message to the audience that this is what you need to do to go from the bottom, straight to the top. There is not one dull or unproblematic moment within the entire film, which keeps the viewers on edge, waiting to see what will happen next.

Although Kashyap and Barjatya have strong differences and polar opposites in their content, it is important to identify what they have that is similar. Both directors are somewhat misogynistic in their representations of women. Barjatya and Kashyap show women through the male gaze, as an object to obtain. Barjatya does this through minimizing the female character’s qualities through primarily looks. Barjatya focuses on showcasing humble and domesticated women that succumb to Indian female stereotypes. Kashyap keeps a misogynistic lens at times through a man’s infliction of violence and nonconsensual sex on a woman. This is shown through the male protagonist, Dev, in Kashyap’s Dev.D (2009). Dev is a spoiled rich kid who is verbally and physically aggressive towards the woman he desires, Paro, and she complies, and continues to chase after him. In the beginning of the film, Dev tells Paro to send him a nude photo, and she goes through several lengths to get the photo taken, developed and sent to Dev in London. When Dev returns to India, Paro sexually asserts herself on him and Dev responds by being both verbally and physically aggressive. This representation shows Paro, not as a human, but an entity for Dev to obtain as he pleases—but it is clear that Dev only wants Paro when she is not easily attainable to him. This same misogynistic lens is used through Kashyap’s characters of Raghav in Raman Raghav 2.0 (2016) and Sardar in Gangs of Wasseypur (2012). In Raman Raghav 2.0 (2016) Raghav is shown having a sexual relationship with Simmy, but whenever Simmy speaks her mind, or tries to initiate an emotionally intimate relationship with Raghav, Raghav is verbally aggressive and dismissive towards her.

Although Kashyap carries this misogynistic lens at times, he also empowers women within his films as well. Comparatively, in his 2009 interview with “India today”, Kashyap stated that he hated the ‘girl next door’ and preferred to depict strong independent women (India today, 2009).

Likewise, in Gangs of Wasseypur (2012), the women are empowered in the form of Sardar Khan’s first wife, Nagma, and at times deemed as a powerless entity to be attained, like Sardar Khan’s second wife, Durga. In the beginning of the film, when Nagma finds Sardar cheating on her at a brothel, she beats him thoroughly, and although it is a form of domestic violence, it is shown from the wife’s side. We see Nagma run after Sardar, throw things at him, and Sardar run from Nagma in fear. In this way, Kashyap is empowering a female character by not only giving her a right to an opinion, but the right to act on it as well.

In comparison, when the audience is first introduced to Durga, we see her in voyeuristic lenses that reflect Sardar’s male gaze on her. Sardar’s initial interactions with Durga do not include her speaking or giving any indication of consent for him to touch her the way he does. Sardar even forces himself on her at one point, and instead of fighting back, she becomes his second wife. After this, Nagma is shown again as a strong female lead regarding her disapproval of Sardar’s actions that are prevalent within her dialogue and demeanor. Only later does Durga stand her ground as well, but she differs from Nagma in the sense that Durga does not directly stand up to Sardar, but she does so behind his back—she gives the assassins Sardar’s location.

What’s interesting about Gangs of Wasseypur (2012) as a whole is that, like Barjatya, it does emphasize the importance of family; however, in a brutally violent context. This film shows the struggles of growing up with nothing and having to fend for yourself and go to any lengths to take care of what is the most important—family. But again, even though Kashyap is similar to Barjatya in this particular film by emphasizing the value of family, he buries this with highlighting the difficulties of families with financial issues, marital affairs, and complications at home—this film is anything but an ‘evergreen’ depiction of family.

Ultimately, the polar ends of Bollywood cinema are the films that contradict each other in the realm of what it means to be in India. Barjatya’s films capitalize on safe Indian stereotypes and ideas of what the ideal Indian family should be like. Although Barjatya’s films are not progressive with India’s times, they are safe and viewable to all audiences, which adds to his commercial success. Comparatively, Kashyap’s films capitalize on showing audiences what he believes to be the ‘real’ India through his sexually and explicity violent lens. And even though Kashyap’s films are representative of the issues prevalent in India today, they face challenges with the censor board and Indian viewers who believe that this content is not suitable for the big screen. So the question is, when going to the cinema in India, would you prefer to be entertained and escape from reality, or be educated and engrossed within reality?

References

Anand, V. (Director). (1966). Teesri Manzil [Third Floor] [Film] Nasir Hussain Films.

Asif, K. (Director). (1960). Mughal-e-Azam [The Emperor of the Mughals] [Film] Sterling Investment Corporation.

Barjatya, S. R. (Director). (1989). Maine Pyar Kiya [I Loved] [Film]. Rajshri Productions.

Barjatya, S. R. (Director). (1994). Hum Aapke Hain Koun..! [Who am I to you?] [Film]. Rajshri Productions.

Barjatya, S. R. (Director). (1999). Hum Saath-Saath Hain [We Are together] [Film]. Rajshri Productions.

Barjatya, S. R. (Director). (2006). Vivah [Marriage] [Film]. Rajshri Productions.

Dutt, G. (Director). (1959). Kaagaz Ke Phool [Paper Flowers] [Film].

Dwyer, Rachel. & British Film Institute. (2005). 100 Bollywood films. BFI.

India today. v.34 no.9-17 2009.(1975). New Delhi: Thomson Living Media India Ltd. (p. 608-610).

Kapoor, R. (Director). (1951). Awaara [The Vagabond] [Film]. All India Film Corporation. R.K. Films.

Kashyap, A. (Director) (2009). Dev.D [Film]. UTV Spotboy.

Kashyap, A. (Director) (2012). Gangs of वासेपुर [Gangs of Wasseypur] [Film]. Anurag Kashyap Films. Jar Pictures.

Kashyap, A. (Director) (2016). Raman Raghav 2.0 [Psycho Raman] [Film]. Phantom Films.

Paunksnis, R. C., & Paunksnis, Š. (2020). Masculine anxiety and ‘new Indian woman’ in the films of Anurag Kashyap. South Asian Popular Culture, 18(2), 149–162. https://doi.org/10.1080/14746689.2020.1773656

Ray, S. (Director). (1955). Pather Panchali [Song of the Little Road] [Film]. Government of West Bengal.

Ray, S. (Director). (1964). Charulata [The Lonely Wife] [Film]. R.D.Bansal & Co.

Roy, B. (Director). (1953). Do Bigha Zamin [Two measurements of land] [Film]. Bimal Roy Productions.

Sippy, R. (Director). (1975). Sholay [Embers] [Film]. Sippy Films. United Producers.

Uberoi, P. (2001). Imagining the Family: An Ethnography of Viewing Hum Aapke Hain Koun...!. Pleasure and the nation: The history, politics and consumption of public culture in India, 309-51.