Going to a film festival can be an experience. It is an opportunity to acknowledge cinematic works or local artists as well as ones from all around the world. However, if presented with a film that was reduced from its original artistic value, would it be as enjoyable? The Censorship Committee within Qatar is in charge of censorship regarding film screenings.

Censorship in Qatar is oriented around articles 62-65 (Al Meezan, 1979). Article 62 explains how the Department of Publications and Publishing is in charge of forming “the Censorship Committee” (Al Meezan, 1979). This committee includes a chairperson, four individuals selected by the Minister of Information, and a representative from the Ministries of Education, Interior, Labour and Social Affairs (Al Meezan, 1979). Article 63 explains how no artistic work can be shown in an open exhibit without a permit from the Censorship Committee (Al Meezan, 1979). Additionally, this article explains how the Committee has the power to delete scenes when the artistic work is viewed, and after doing so, the Committee issues two permits (Al Meezan, 1979). Article 64 explains the relationship between the Department of Publications and Publishing and the Censorship Committee. Furthermore, the Department of Publications and Publishing directs the Censorship Committee in order to ensure proper standards of technical, social, religious, and ethical and cultural traditions within artistic works (Al Meezan, 1979). Finally, article 65 explains how the Censorship Committee needs to conduct proper inspections of venues of film screenings in order to verify its compliance and distribute permits (Al Meezan, 1979).

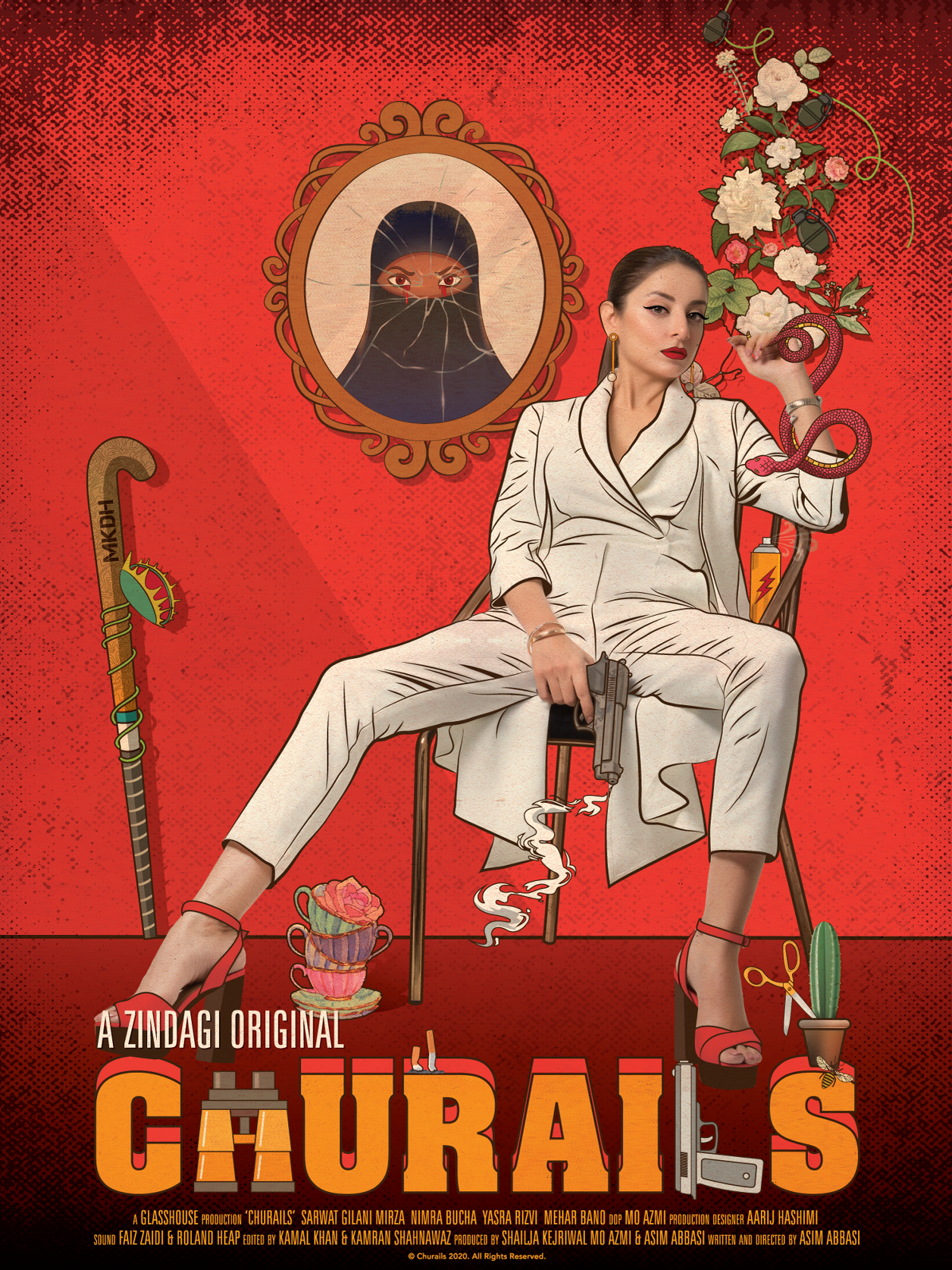

Even when it comes to film festivals within Qatar, such as Ajyal, the Censorship Committee maintains control over censorship within the festival. In particular, Doha Film Institute (DFI) is experiencing issues relating to the censorship of film screenings in film festivals. Furthermore, DFI is looking for help in negotiating censorship laws within film festivals, and hopefully change the way the Censorship Committee is created and functions. The reason DFI is focusing only on improving censorship regulations within film festivals and not a broader spectrum is because of its feasibility. Film festivals cater towards audiences who are eager to see artistic works screened in their entirety within film festivals. In this way, it would be difficult to expand the argument towards a broader spectrum as all cinemas around all cinemas in Qatar because this demographic differs from those attending film festivals. Likewise, those going to the cinema for fun are better accustomed to censorship regulations and extensive cuts of films, and are not as eager to fight for changes in censorship laws. The use of censorship within these film festival screenings is causing a misinterpretation of the artistic work, and therefore, frustrating both audiences and the filmmakers themselves. DFI is addressing censorship issues amongst both local and foreign filmmakers. Although censorship varies amongst the two, it is important to analyze the ability to limit censorship amongst artistic works screened by both types of filmmakers. Ultimately, not being able to view the entirety of films takes away from its artistic and cinematic value. When determining the correct course of action to combat extreme censorship in Qatar, it is vital to analyze similar experiences from film festivals around the world.

For example, in China, films, within film festivals, undergo initial censorship when reading the screenplay and the feedback is given in twenty days or less (Rapold, 2019). Previous instances at film festivals in China have proven that banning popular films from screening, and censoring them, has disappointed audiences’ various times (Hancock, 2019). “Typically, films that touch on sensitive issues like foreign affairs, the military, police or public security organs, ethnic minorities or religion pass through additional “special channels” of censorship, sources tell Variety. For instance, Hollywood sci-fi blockbuster “Arrival” needed special approval from the Chinese military before it hit mainland theaters because it featured a Chinese general” (Davis, 2019). Similar to what the Censorship Committee searches for in Qatar, censorship in China looks for similar aspects. It is intriguing to see that Hollywood films undergo the same process, despite their popularity and success, when being screened in China. “China’s top film regulator was merged with the ruling party’s propaganda department last year, a move that several film industry executives said had resulted in a tightening of China’s already restrictive film censorship” (Hancock, 2019). Considering how the Communist party has majority control over film regulations and censorship, it has been difficult to combat this issue in China. Chinese cinemas have experienced an extreme drop in its revenue and entertainment market due to the extreme regulations made towards films (Hancock, 2019). In China, this is being “combatted” by filmmakers who are succeeding in film festivals in other parts of the world, after being censored or banned at Chinese film festivals. In the future, China may see the decline of their film industry and the success of past potential films being released elsewhere, as a lessen to reduce their censorship laws. It is interesting to compare and contrast China’s history of extreme censorship within film festivals to other instances around the globe, because unlike China, others have grown in their leniency regarding censorship laws.

In Cuba, there has been a similar use of excessive film censorship in film festivals. Films has been banned from film festivals in Cuba due to “sensitive” topics that have managed to gain controversy over social media (Courtesy, 2017). There are people who agree with the censorship and others who do not. The spread of controversy over social media has demonstrated amongst the public in Cuba that there are many opposed to the use of censorship within these artistic works for various reasons. Despite much critical acclaim of independent films in Cuba, they have been extremely censored or banned, therefore, independent filmmakers have begun to take a stance (Reuters, 2019). This instance helps us realize the many different demographics these screenings cater towards. One of them being the filmmakers themselves, and how their artistic work is not being accurately represented on screen due to censorship. “In a country that has been dominated by the state since the leftist revolution of 1959, it was long up to the Cuban Film Institute (ICAIC) to produce and finance movies” (Reuters, 2019). Now, Cuban filmmakers have made films outside the state, diverting excessive censorship, and establishing independent filmmaking practices (Reuters, 2019). Although still in the midst of some censorship laws and regulations, Cuban filmmakers have been able to establish partial artistic freedom when it comes to creating films (Reuters, 2019).

Despite years of restrictions, Iran is slowly escaping censorship within its film industry as well. Due to the extremely conservative society, films and Iran have a long history of being banned (Khadem, 2017). “But staying in Iran means constantly testing boundaries of Islamic propriety. After the revolution, movies were banned for being sources of what the new regime saw as foreign corruption and imperialism. In his first year as Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini banned more than 500 foreign films” (Khadem, 2017). After gaining Western attention for being banned, the censorship and limits among Iranian films has eased over time (Khadem, 2017). Films not only gained several nominations, but won Academy awards as well (Khadem, 2017). By gaining several awards as well as global recognition, banning has eased amongst Iranian film festivals. “Another Panahi film in 2000, The Circle (Dayereh), which criticises the treatment of women in Iran, was also banned. Again, the film won several awards despite its suppression, including the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival that year” (Khadem, 2017). Filmmakers continue making "good movies" that resonate with wider global audiences, they also consciously or unconsciously become part of change in Iran.

Both recommended courses of actions are influenced by factors that have helped ease censorship laws in Cuba and Iran. The public opinion has played a huge impact whether it has been shown through social media or the audience’s actions themselves. The first recommendation would be to analyze the social media demographic. Therefore, looking at past and present public reactions from censorship with Qatar film festivals. Then it will be possible to compare and contrast positive versus negative opinions towards censorship. This analysis of data on social media will help to determine a correct course of action.

Another recommended course of action would be to create a diverse group the censor. Although Qatar already has a Censorship Committee in place, it would be more impactful to have a committee that more accurately represents the audiences of film festivals within Qatar. The focus group would encompass residents of Qatar, who enjoy film festivals, and are of a variety of different ethnic backgrounds. Within these focus groups, possible films to be screening within the film festivals would be screened in front of the focus group. The focus group would then provide their opinions pertaining to censorship. Because of the cultural atmosphere of Qatar, it is impossible to eliminate censorship all together, however it is possible to combat the cultural bias and make censorship more lenient and adjusted to the catered demographic.

Prior to choosing the correct recommended course of action, it is important undergo aspects of the PESTLE analysis, such as political, economic, social, technological, and legal factors. Politically, these recommended courses of actions allow responses to be more accurate and less influenced by governmental control. This is because the ways we are suggesting to go about censorship are more representative regarding the film festival demographic’s opinions on censorship. Likewise, although film festivals in Qatar operate locally, they cater to international platforms. The economic sector belongs to an independent institution funding film projects along with the venue hosting this film festival. Therefore, it is not extremely valued in the Qatar economy because Qatar has numerous other outlets that they rely on more to benefit their economy. Socially, in Qatar, culture plays a large role in regulating artistic works. However, when looking at a film festival in Qatar, it is important to acknowledge its potential global impacts as well. This can broaden the scope in which the business of film festivals in Qatar operate. Technologically, we are analyzing the screenings themselves, films being projected in cinemas during film festivals. Regulations could also be applied within further distribution of the films, such as on DVDs or streaming platforms. However, technological innovations should not have a large influence on the market because Qatar does not have a history of regulating content when it becomes digitally available. Finally, legal regulations are related directly to the Censorship Committee, however it is not specified what specifically in films, warrants a cut from a film: most likely, violence, nudity, language, etc.

Ultimately, based off of my previous analysis of censorship within film festivals around the world, it can be determined that the audiences’ opinions have a large influence over the leniency within censorship laws. In this way, by implementing one of the two recommended courses of actions, we can negotiate Qatar film censorship laws in a way that benefits filmmakers as well as the catered demographic.

References

Al Meezan—Qatary Legal Portal | Legislations | Law No. 8 of 1979 on Publications and Publishing. (1979). Retrieved December 2, 2019, from http://www.almeezan.qa/LawArticles.aspx?LawTreeSectionID=3123&LawID=414&language=en

Chinese censorship is stifling country’s film industry. (2019, July 11). Retrieved November 29, 2019, from South China Morning Post website: https://www.scmp.com/news/china/society/article/3018159/chinese-censorship-stifling-countrys-film-industry

Davis, R. (2019, May 14). China’s Censors Confound Biz. Retrieved December 1, 2019, from Variety website: https://variety.com/2019/film/spotlight/china-censors-film-1203213140/

Hancock, T. (2019). Censorship casts shadow over China’s top film festival. Retrieved November 11, 2019, from Financial Times website: https://www.ft.com/content/30c4425a-90d9-11e9-aea1-2b1d33ac3271

Khadem, N. (2017, November 9). Iranian regime’s censorship of films is easing, says director Hamid Nematollah. Retrieved November 11, 2019, from The Sydney Morning Herald website: https://www.smh.com.au/national/iranian-regimes-censorship-of-films-is-easing-says-director-hamid-nematollah-20171107-gzgoei.html

Newman, L. (2018). At Havana film festival, Cuban filmmakers fight censorship. (n.d.). Retrieved November 11, 2019, from https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2018/12/havana-film-festival-cuban-filmmakers-fight-censorship-181216102501313.html

Rapold, N. (2019, August 27). Making a Movie and Surviving China’s Censors. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2019/08/27/arts/venice-film-festival-lou-ye-china.html

Reuters. (2019, June 28). Cuba finally legalizes independent movie-making—But censorship still an issue. Retrieved November 11, 2019, from New York Post website: https://nypost.com/2019/06/28/cuba-finally-legalizes-independent-movie-making-but-censorship-still-an-issue/

Torres. N. (2017). A Cuban film about gay repression pulled from festival. Was it censorship? Retrieved November 11, 2019, from Miamiherald website: https://www.miamiherald.com/news/nation-world/world/americas/cuba/article139831628.html