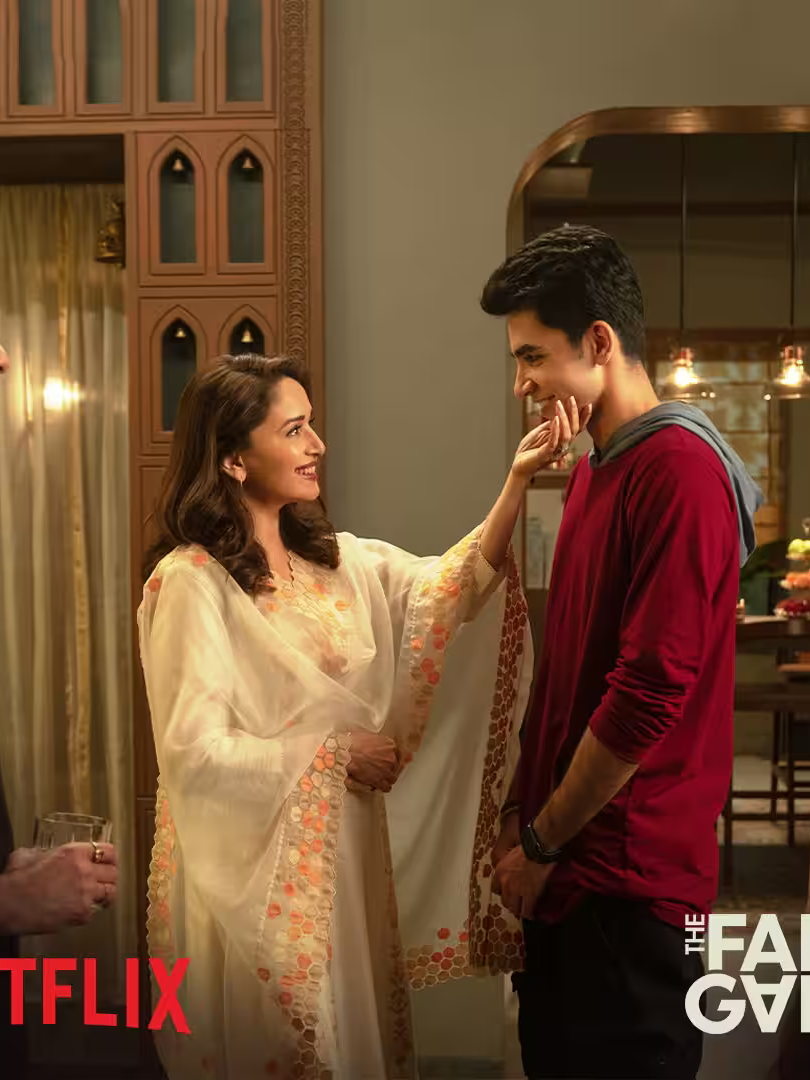

Personal Connection

When I was fifteen I spent two consecutive years doing freelance media work at various television networks and media companies in Karachi, Pakistan. It was there that I got the chance to fully immerse myself in the Pakistani media industry. This is the very same media industry that myself, and others in the Pakistani-American community, assumed to only consist of melodramatic television serials and loud newscasters. It was only through these experiences that I realized the large variety in media content that Pakistan possessed, and how it had so much potential beyond its local masses.

Aneesa Khan at the Coke Studio - Season 10 Premiere in 2017.

History of Pakistani Cinema

Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq became Dictator and President of Pakistan in 1977, he later established the Hudood Ordinances in 1979. The Hudood Ordinances were a set of laws made to begin “Islamization” in Pakistan. Once established, the ordinances not only restricted the liberties of women, but also the frequency of the nation’s film, musical, and theatrical productions.

Over the next decades, as leadership within Pakistan changed, so did Pakistan’s identity in media. Pakistan’s media industry then encompassed frivolous morning shows, angry news interviews, and mostly, drama serials.

As a first-generation American, with Pakistani immigrant parents, you grew up with this restricted variety of content blaring on the television screen of your home every day. Over time, Pakistan’s dramas garnered attention and acclaim all over the world. This is mostly attributed to streaming services such as Netflix and YouTube reviving these dramas and diversifying their audiences. The success of Pakistani drama serials allowed for a slow progression to telefilms, and then the inevitable revival of the Pakistani cinema industry: Lollywood.

After a prolonged stand-still, Zinda Bhaag (2013) was the first film submission from Pakistan to the Oscars in fifty years. Following this, Na Maloom Afraad (2014) sparked the revival of the Pakistani cinema industry (Lollywood), with its international feature-length release. Then came Pakistan’s first cinematic blockbuster after its hiatus, Bin Roye (2015). While Bin Roye (2015) capitalized on its commercial and romantic appeal, Na Maloom Afraad (2014) flourished in critical acclaim. What followed was a newly instilled determination from filmmakers in Pakistan to create both commercial and art films, with multiple films being produced and released in Pakistan every year.

Na Maloom Afraad (2014): In an effort to achieve their wealthiest dreams, three clueless men join forces to take down a don.

Bin Roye (2015): After a tragic accident, a woman is forced to act on her feelings for her brother-in-law.

South Asian Content in Relation to Success in the Western Sphere

The success of South-Asian films has been equated with its scope for globalization ever since the colonialist era. This is illustrated by the pedestal that Priyanka Chopra is put on by the public by “straddling both Hollywood and Bollywood.” Actors like Fawad Khan and Mahira Khan are commended on the same premise, but for the fact that they worked in Bollywood and have garnered success there along with Lollywood.

Pakistani Actress, Mahira Khan in the Bollywood film, Raees (2017) with “King of Bollywood,” Shahrukh Khan.

But the main question that has yet to be analyzed and answered is: Why hasn’t Lollywood garnered success and attention beyond Pakistan?

Many can blame Pakistani dramas and news for Pakistan’s lack of success in the diasporic market. Likewise, the political jokes and cultural references are subject to an understanding amongst the Pakistani audience in Pakistan. So how do we instill faith in Pakistani cinema outside of Pakistan? Well first, it’s important to distinguish differences in the storylines and executions between drama serials and films. It's easy to group these two categories together because Pakistan’s most famous actors garner their success from dramas and then capitalize on this success when transitioning to films.

However, it’s always been a struggle to give Pakistani media a chance beyond what our families blast on living room television screens. Comparatively, Bollywood cinema has flourished in the United States, even beyond its Indian-American demographic.

With that in mind, there is a strong need for Pakistani cinema to cater to the broader masses. One director who’s made a clear mark in the Pakistani film industry is Nabeel Qureshi. Since 2014, director, Nabeel Qureshi has been able to develop his own clear style. Qureshi’s directing and writing style is the perfect combination of comedy and political satire. Every film he directed acts as an understated piece of social commentary on Pakistan’s various layers: the caste system, economic instability, and political turmoil.

However, Qureshi’s films are another example of how Pakistani films are primarily made for Pakistanis.

Recently, JORE got the chance to speak with filmmaker Nabeel Qureshi and get his take on the trajectory of Pakistani cinema.

Director Nabeel Qureshi

Aneesa Khan: “So moving forward, how do you think Pakistani films are performing outside of Pakistan? What role do streaming services play in this?”

Nabeel Qureshi: “Pakistan has been a growing media industry. So it will take its good time so it reaches the OTT audience and even, you know, the audience in Pakistan as well. Because unfortunately, if I’m very honest, in a year it's only like 3 or 4 Pakistani movies which are watchable and which you enjoy. The rest of them are not as good in terms of quality, and in terms of aesthetics. In terms of stories, there are major flaws. And in today's world, the audience is not a fool. They have a lot of choices like Netflix, Amazon and everything else. Like what if, for example, there is a movie which is released internationally and you convince your friend to go and watch this movie, and that movie is bad. That person will not go and watch a Pakistani movie again. As a film industry or as a filmmaker, we need to make better quality films, better stories, and our films should look like films, not like a TV drama. That's actually impacting knowing a lot of audiences not coming to cinemas, internationally or locally.”

Aneesa Khan: “We are talking a lot about better narratives and better stories. According to that, I feel like we, in Pakistan, make films for Pakistanis in Pakistan so that if someone from another ethnicity were to watch it, they're not going to understand the political jokes or the social jokes, etc. So is there a way that we can adjust the narratives to fit a broader demographic?”

Nabeel Qureshi: “You are absolutely right. There are, you know, some connotations in the movies, some jokes, which are very I would say "Karachite" or Pakistani which does not have relatability abroad. So that depends on the makers who make it and what kind of story you are telling. But, for example, in my movie, ‘Quaid-e-Azam Zindabad,’ corruption is the most popular and most relatable thing. And I think overseas Pakistanis can relate to it more than the Pakistanis that are living in Pakistan. Because they've been watching that on the news and after the kind of political turmoil that Pakistan is going through. So corruption was quite relatable I think that probably works because ‘Quaid-e-Azam Zindabad’ did very well internationally.”

Aneesa Khan: “What do you predict for the future of Pakistani cinema? What should our goals be in terms of content?”

Nabeel Qureshi: “Yes, content has to play an important part. And I'm very hopeful because of the kind of new filmmakers in Pakistan. The kind of films of this time, the kind of stories they are making. We are totally on the right track. Probably, in the next 10 years, in the Pakistan industry, our stories can be much appreciated and more, you know, relatable and more unique. And we will have our own identity.”

What's Next? Where Do We Go From Here?

Since the revival of Pakistani cinema in 2014, Pakistan has continued to push the boundaries of its content both inside and outside of Pakistan.

In 2012, Sharmeen-Obaid-Chinoy became the first Pakistani to win an Oscar and again in 2016. Both wins for her own short documentaries pushed the boundaries in terms of Pakistani narratives.

In 2020, Churails, a Pakistani web series about feminist detectives, was released on an Indian streaming platform, Zee5. The unconventional premise of the show garnered a lot of attention from viewers. However, this [very unconventionality] pushed Pakistan to ban the series from being viewed in Pakistan.

As recently as this year, Joyland (2022) became the first Pakistani film to screen at Cannes International Film Festival and won the Jury Prize in the Un Certain Regard category. Since the film’s success and debut at Cannes, the film has garnered international acclaim and has been submitted as Pakistan’s official submission at the Oscars.

In this way, Joyland’s international success may be the beginning of more attention toward Pakistani content beyond Pakistan’s borders. In this way, it’s a statement on its own that the Pakistani content that is the most unconventional is garnering the most attention and acclaim for the region.

Most recently released from Pakistan, The Legend of Maula Jatt, created by Bilal Lashari, and starring Pakistani icons such as Fawad Khan, Hamza Ali Abbasi, and Mahira Khan, has been making waves in the box office. This film has been in the making for the past nine years, with the largest production budget of any Pakistani film to date. The anticipation of the film is credited to the star power star in its cast and the dedicated fan base behind the original Punjabi-Pakistani folklore that was picturized in 1979. Since the film’s recent release, it has made a record number at the global box office and is receiving rave reviews. Likewise, following the international success of Joyland, it is possible that the success of The Legend of Maula Jatt acts as another stepping stone for Pakistani cinema’s outreach beyond Pakistan. Finally, the world is beginning to see the beauty of Pakistan and our culture on the big screen across the globe.